It’s a cloudy afternoon in Athens, where Horvath has lived for over four decades and has become a local legend in the small Southeast Ohio town. His snow white hair, well-trimmed beard and circular glasses give Horvath, 72, an indelible look that matches his easy-going, personable vibe.

But not many Athens residents see that side of him.

Usually, they usually just hear the voice of Horvath, the public address announcer at nearly every Ohio University athletic event and the lead vocalist in a classic rock band that draws locals to each gig.

His story, however, goes far beyond his baritones, which is why Horvath set down his sandwich after one bite.

He always has a lot to tell.

“Oh, hell no,” he said when asked if his life as a PA announcer has ever grown old. “It’s a privilege. It’s elation. The only problem is people move on.”

He’s right. Plenty of people have moved on across his 20 years as the voice of Ohio athletics. That’s what happens in a college athletic department, where the typical career of a student-athlete is four years.

Horvath, born and raised in Bellaire, has lived in Athens since 1971. He’s here to stay. For him, Athens is the perfect town, and anyone who’s attended an OU sporting event or heard one of his musical acts won’t forget about him.

“This is my adopted community...I spent more time here than in any other place in my life. The ability for our organization to give back to the community and recognize those people who made the ultimate sacrifice, that meant a great deal.”-Lou Horvath

With Horvath, something new is always there to discover.

Ohio men’s basketball coach Jeff Boals shimmies down the sideline and pumps his arms at the fans sitting a few feet behind his team.

Between Boals and the crowd is Horvath. He’s sitting with two hands firmly placed atop the scorer’s table and shouting into the black earpiece lined along the right side of his cheek.

He’s excited, too. His voice echoes through The Convo as the Bobcats race up and down the court between each play. Horvath’s job is to ensure the crowd can feel the same energy as him.

“Jordan Dartis, from the third ring of Saturn!”

“Put! Back! Slam! Jason Preston!”

Horvath is unconventional. He prefers not to follow the typical linguistics most PA announcers use.

For basketball, his Saturn reference and thunderous pronouncements when a player dunks stick out most. For volleyball, Horvath bounces around nicknames with each player — “Leapin’” Lizzie Stephens, “Jumpin’” Jamie Kosiorek. For football, he constantly urges the crowd at Peden Stadium to “get agitated!”

He sprinkles in his own blend of phrases for each sport. That’s, perhaps, the biggest reason so many Ohio fans know Horvath.

“Way back in the day when I first heard him, I thought it was cool and neat,” said Rick Hartung, 73, who’s attended games in The Convo since the ’70s. “But I thought, ‘Man, can he keep that up?’”

Horvath certainly has. He wants everyone to know he doesn’t script his phrases and monikers, either. They flow freely. When he feels the time is right for one, he just says it.

“If you haven’t noticed, I’m not exactly the quietest guy,” Horvath said with a smile. “I’m not an NBA cookie-cutter guy that yells, ‘Threeeee.’ If I ever do that, just drag me off.”

Horvath first broke into PA announcing for his son’s junior high school soccer games at Alexander High School in the late ’90s. He was so good that the school eventually asked him to be their basketball announcer, too, and it’s a role he still has today.

Horvath followed Alexander to The Convo when the team played in a tournament inside the now 51-year-old building. For the tournament, Horvath sometimes completed eight games in a day.

So, he couldn’t help himself when he overheard someone from the Ohio athletic department at a scrimmage soccer game at Peden Stadium.

“If we could just find somebody to announce these games,” he said.

Horvath was sitting behind him and tapped him on the shoulder.

“Hey, I’m Lou,” he said. “I can do this.”

His role expanded to men’s and women’s basketball, volleyball and football, which he began 10 years ago. He’s still the announcer for each of those sports and has rarely missed an event across his two decades with OU athletics.

Players have noticed when Horvath isn’t there. His most recent absence was for three Ohio WNIT games last season when he took his family on vacation to Italy.

“It was definitely weird not having Lou here,” guard Dominique Doseck said in a postgame interview March 21 against High Point. “That was … odd, especially in warmups.”

Coach Bob Boldon missed Horvath, too.

“I think everyone misses Lou,” Boldon said. “That gave us a peek into what retirement might look like without Lou here.”

Horvath’s absence was only temporary. He doesn’t plan on permanently vacating his seat anytime soon.

“As long as I can still think and talk,” he said when asked about how much longer he’ll go. “As long as I can put a phrase together.”

Provided by Shelly Horvath

Lou Horvath from when he was in the Army and served in the Vietnam War in the late 1960s.

Before he began a life tucked into the Southeast Ohio portion of Appalachia, Horvath endured a brief but important period of time in Pleiku, Vietnam.

Horvath is a Vietnam War veteran. He is open to discussing his experiences — and opinions — from his time as an intelligence analyst for the U.S Army. He spent 18 months on tour after a high school friend convinced him to forego his engineering degree at Indiana Tech and enlist upon being drafted.

At the time, Horvath only wanted to join the Army Security Agency. He was told the ASA didn’t operate in Vietnam. Instead, Horvath could visit Rome or Athens, Greece.

Horvath soon learned that was all for show.

Turns out, the ASA did operate in Vietnam. The recruiter just referred to them with a different name: “Radio Research.”

Horvath didn’t know that, though. Soon enough, he was heading to Pleiku. The war was reaching its peak, and he was part of hundreds of thousands of American soldiers boarding an 18-hour flight to the battlegrounds.

“We were scared,” Horvath said. “Everybody was scared. You get on the airplane, look down, and it’s frightening. You see smoke billowing in different places. You hear shots. You hear sirens.”

Horvath’s duties didn’t require him to fight in combat, but he still had a close-up view of the carnage. When he describes one of them, it’s not with a disappointing, sorrowful tone a listener might expect.

Instead, he cracks a smile.

The date was Sept. 12, 1968. Horvath and his crewmates were settling into a station located on a red dirt hill three kilometers outside of Pleiku. The base was not fully developed. Soldiers had bed spreads stuffed with feathers instead of mattresses, and the area looked much different from a typical barracks.

On that calm night, Horvath and his crewmates were hit with 110 mortar shells that fell within the length of a football field around their base. In training, they were told to use their mattresses as shields in an attack.

They didn’t have those. The only cover was their thin bed linens.

As bombs exploded the area around him, Horvath looked over to his friend, John Miller, and laughed.

“Miller!” Horvath yelled. “We’re supposed to roll over on our butts and cover up with a mattress. All we have is sleeping bags. If we get hit, there’s going to be feathers everywhere!”

Miller looked back at Horvath, nicknamed “Hoover,” and delivered a grisly reply.

“Hoover,” he said, “if we get hit, there will be red feathers!”

The rest of the crew laughed as explosions continued to bludgeon the land around them.

None of the men Horvath knew were hurt, and he escaped the end of his 18 months without any wounds or long-term health problems.

But the fallout of the war and whether the U.S. should’ve been involved have always given Horvath mixed feelings.

“There’s kind of a suspicion in how things work,” Horvath said. “There’s a bit of a chip on your shoulder ... We picked the wrong side, I think. If you read back through history, we chose the more corrupt of the two sides.”

Horvath struggled to cope with the U.S. involvement in the war until he watched the movie Apocalypse Now in the Athena Cinema in 1979, nearly a decade since he was in Vietnam.

Before then, he and other veterans felt a sense of regret for serving in the war. People from both ends of the political spectrum were skeptical of the war efforts, and that limited the level of pride Horvath felt for being a Vietnam veteran.

But the movie, which details the tumultuous journey of a U.S. Army officer’s pursuit to assassinate a Special Forces colonel, helped Horvath come to grips.

After watching the film, Horvath remembers walking outside the cinema and sitting on the curb. He was lost in thought.

So, too, was another man across the street who watched the film and was pacing around the parking lot.

“That was another veteran,” Horvath said. “We were reflecting on those things we experienced. (The movie) pretty much captured the feeling that we didn’t exactly know where we were going. There was always an underlying sense of uneasiness and foreboding. That allowed me to vent and put things in perspective.”

Unlike some other veterans, Horvath doesn’t carry a bucket list of tasks he feels he should do after spending a fraction of life in war.

Provided by Shelly Horvath

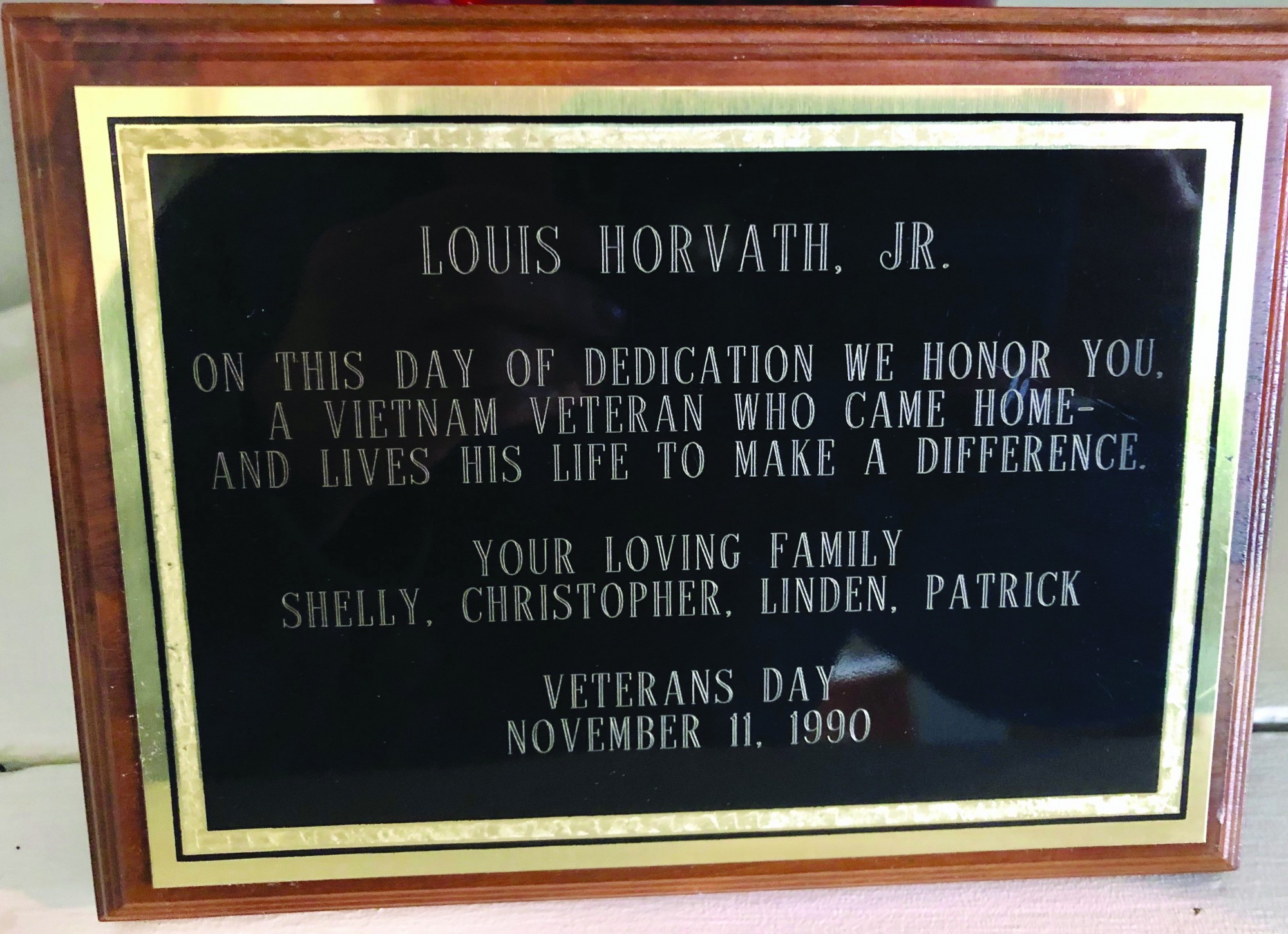

A plaque Lou Horvath received from his family after a Veterans Day memorial service he helped plan in Athens in 1990.

To him, Athens has given him everything he’s wanted, anyway. He’s been married to his wife, Shelly, for 31 years and has watched his three kids grow up and call Athens home. Horvath held a Social Security job after his military service. He is now retired.

He’s also ensured that the courage of Vietnam War veterans won’t be forgotten in his town.

One of Horvath’s proudest achievements can be seen on the bricks of the Athens County Courthouse, where the Athens Area Vietnam Veterans of America chapter raised money to place a bronze plaque with 31 names of Athens residents and OU students who died in the war.

The plaque was added to the building in 1990. Horvath was one of the chapter’s members who led the fundraising efforts and reached out to each of the veterans’ families listed on the plaque for an invitation to the memorial ceremony.

“This is my adopted community,” Horvath said. “I spent more time here than in any other place in my life. The ability for our organization to give back to the community and recognize those people who made the ultimate sacrifice, that meant a great deal.”

Horvath received a plaque of his own, too.

It was from his family, who gave it to Horvath on the day of the ceremony and wanted him to have a personal piece of memorabilia for his service. It currently sits in his home office.

“On this day of dedication, we honor you,” the plaque says in gold engraved script, “a Vietnam veteran who came home — and lives to make a difference.

The Smiling Skull Saloon is mostly quiet. A few bargoers — ranging from OU college students to older Athens residents — sit in wooden chairs around the dimly lit bar and chat over a playlist of Johnny Cash songs playing over the speakers.

Then, the music stops. Horvath breaks the silence as he stands on a stage with his five other band members.

“For those who don’t know who we are, that’s good — because you can’t put it in a subpoena,” Horvath jokes after grabbing his light brown Music Man guitar and making a practice strum.

Horvath is in a light blue Hawaiian shirt decorated with dark blue flowers. Underneath is a black long-sleeve Ohio Bobcats football T-shirt.

It’s Horvath’s traditional attire when he performs at The Skull with his band, Backwords. The band performs dozens of classic rock and soul hits about once a month, and it’s another way that Horvath has built his fame around town.

“Every time I see Backwords is playing, I’m here,” said one woman, facing the stage and tapping her foot to the music.

Anthony Poisal | SPORTS EDITOR

Horvath sings with his band “Backwords” inside The Smiling Skull Saloon.

Her husband is sitting next to her and nodding his head to the beat.

“They’re the local guys,” he said, “and we like that.”

It doesn’t matter who watches, though. Horvath feels at home.

He’s felt that way ever since he returned from Vietnam in 1970 and moved to Athens. He’s also made Peden Stadium, The Convo and basketball gyms in Southeast Ohio his second homes, too.

Horvath’s voice has become as recognizable as “Stand Up and Cheer” at Ohio sporting events. He loves his job, and people can feel it.

So, after his opening remarks, Horvath looks back and receives the nod from his bandmates for their first song. He steps up to the mic and serenades the crowd with the opening lyrics of “634-5789” by Wilson Pickett.

If you need a little lovin'

Call on me all right

If you want a little huggin'

Call on me baby, mmmmmm

Oh, I'll be right here at home