There is a time and a place for everything.

For graffiti artists in Athens, that place exists at the corner of Mulberry Street and Richland Avenue, where three 20-foot walls exist for the sole purpose of housing graffiti — both of artistic and informative intent.

As spray paint has found its way off that wall and into alleys throughout town, city and university officials as well as residents seem to have differing opinions on where the line is drawn between art and vandalism.

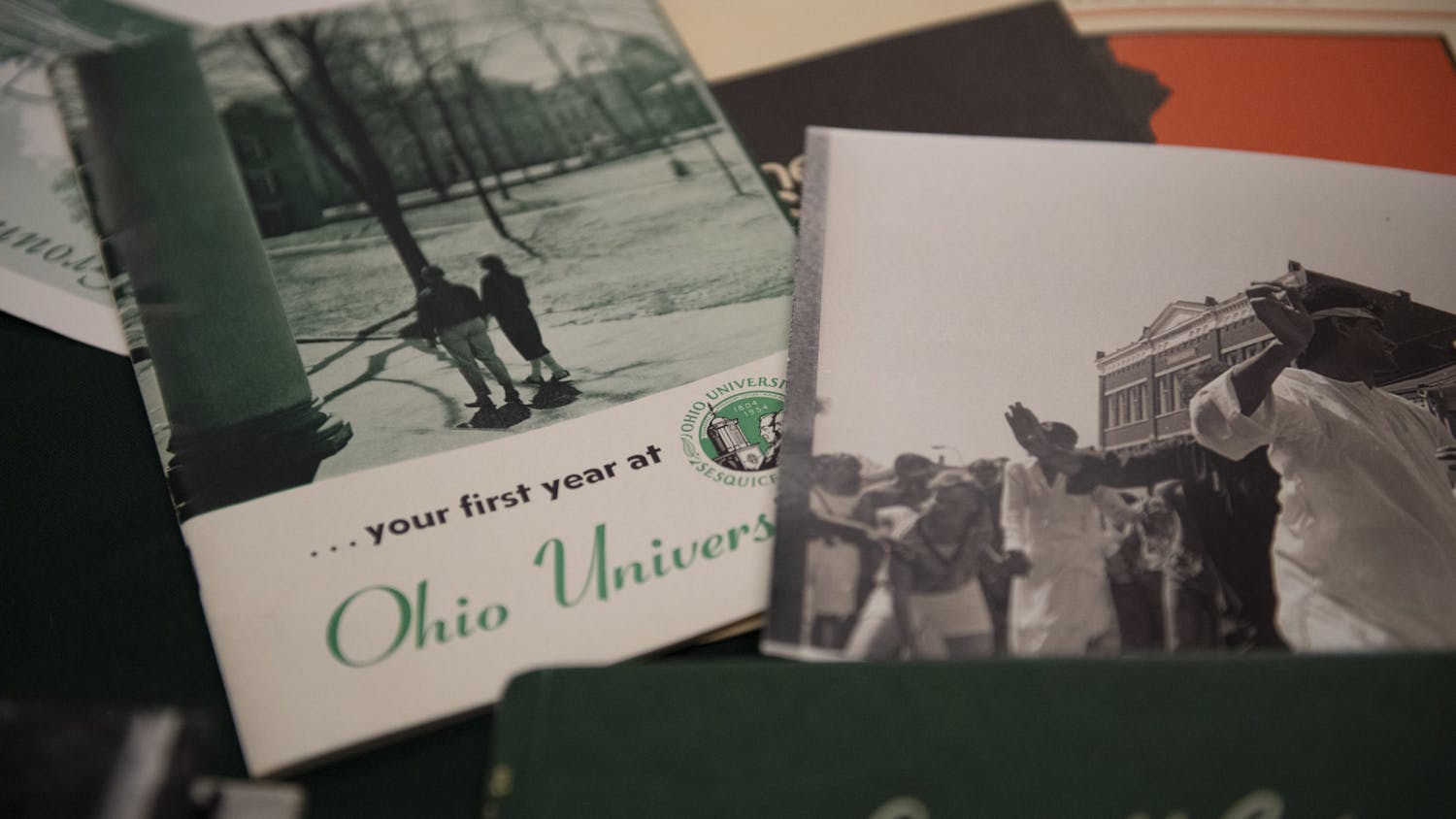

Most agree that the wall, commonly referred to as the “graffiti wall,” is a great place to harbor public art. It was renovated more than a decade ago when the university decided to keep it intact along the backside of Bentley Hall’s annex for just that purpose.

“The graffiti wall was here when I came over 23 years ago,” said Assistant Dean of Students Charlene Kopchick. “When they did renovations of buildings near the wall, the university took steps to preserve the wall so students could publicly express their thoughts and concerns.”

As early as the 1970s, the wall was used for everything from

artistic and political declarations to marriage proposals. When Bentley Hall underwent construction in the early 2000s, space was put aside for a new wall. Anyone is allowed to paint there, and many student organizations see it as a free way to advertise upcoming events.

“We believe in freedom of expression at Ohio University, that’s why we have the graffiti wall,” Kopchick said. “Students are able to express themselves in an appropriate place. That’s why we have a graffiti wall. The only place graffiti is allowed on campus is the graffiti wall.”

Strictly university property, some permanent Athens residents, such as Councilwoman Christine Fahl, rarely venture toward that part of town and maintain a very split view on public art.

“It’s a hard subject,” Fahl said. “On one level, public art is really important. … I think that where it becomes a problem is it doesn’t get done for reasons of art, it gets done for reasons of pegging territory and doing other things that aren’t necessarily creatively inclined.”

Though it’s relatively easy for one to get their hands on a spray-paint can, it is the intention of the painter that differentiates graffiti and art, said Akil Houston, an assistant professor of African-American studies at OU.

“It’s artistic, political, and can be both, depending on the context and who’s doing it,” said Houston, who teaches a class about African-American art and artists, which touches on graffiti culture.

Not all artists and vandals have stuck to the university-mandated wall, and technically all graffiti and tagging elsewhere is considered vandalism.

“What pisses people off in my ward is when people do a bonehead thing,” Fahl said. “There’s a difference between art on a graffiti wall and … penises on rental units.”

At its worst, vandalism can cost an offender more than $150,000 and up to 12 months in prison, according to Ohio Revised Code.

Both the city and OU have made attempts to keep Athens clean, as an Athens City ordinance passed in 2008 requires residents to remove graffiti from private residences. In addition, on Feb. 8, a new university policy to monitor who can chalk and where on campus went into effect, aiming to control, at the very least, chalk graffiti.

“Someone associated with the university — it could be students or a student group — can make people aware of an issue or advertise an event by using sidewalk chalk to write a message,” Kopchick said. “And they’re only allowed to use chalk because it washes away in the rain. They’re not allowed to do that on Athens sidewalks. That’s considered graffiti.”

Students cannot chalk on bricks, vertical services or places with an overhang — and that’s only if the student is using sidewalk chalk, she added.

The main reasoning behind the new rule is to keep OU’s campus clean, said Ryan Lombardi, OU’s dean of students.

“The policy is necessary to minimize the impact on facilities to clean up chalk where it is not appropriate to be placed,” he said.

For some, such as Tristan Menningen, a senior studying special education, seeing a piece of graffiti can brighten one’s day.

“There’s a cool one by my house,” Menningen said. “It’s on a garage door and it says, ‘I have something to say.’ I see it every day and it makes me smile. I think, so long as it’s not profane, it’s fine. I think it’s beautiful.”

jf392708@ohiou.edu

bc822010@ohiou.edu