A body was found inside a home.

The suspected gun used has had its serial number filed off. The bullet has been recovered and needs to be compared to known bullets fired from the gun and another found in the house.

It was a scenario Ohio University’s forensic chemistry program students needed to solve.

The students in this particular lab exercise had to determine whether the wound was self-inflicted and if the bullets were fired from the gun found near the victim.

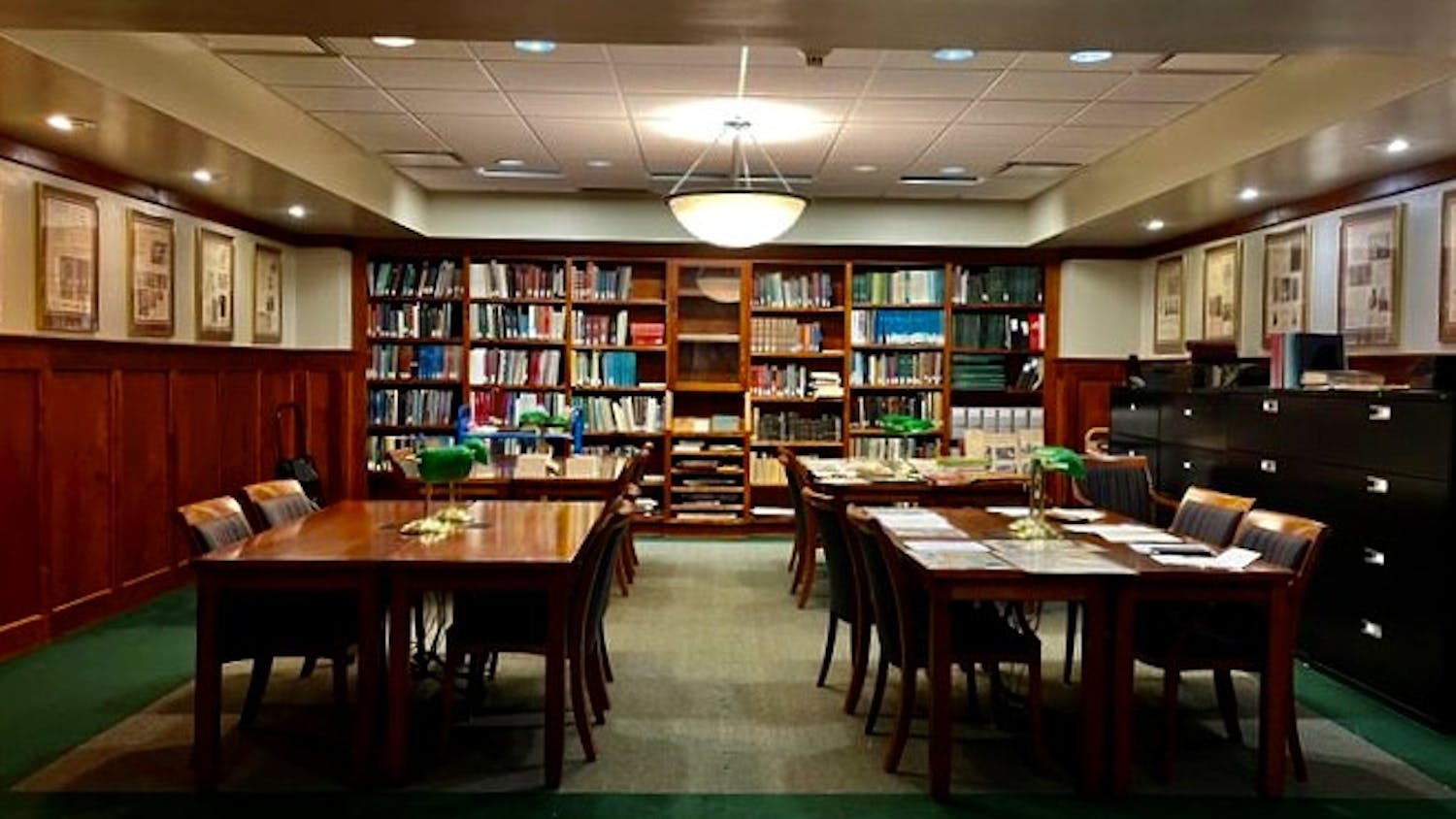

For this case, the team used microscopes to examine the fired bullets — shot by an OU staff member volunteer — and compare the grooves and landing spots of bullets found elsewhere in the scenario.

“We usually run experiments,” said Jules Guei, assistant professor in analytical and forensic chemistry. “It’s exactly like a real forensic lab. Students are learning the same techniques and procedures.”

Students used a chemical process to analyze the gunshot residue, some of which is made up of inorganic nitrites, lead and, with testing, can determine what sort of ammunition was used at the scene of the crime.

The program is one of only five accredited undergraduate programs within the U.S., having first receiving accreditation in 2006, said Peter Harrington, director of the forensic chemistry program.

Forensic chemistry labs don’t cost OU students more than basic chemistry labs, Harrington said.

In the 2012-13 school year, slightly more than 70 students were in the program; nine graduated with jobs, such as employment with the Newark State Police.

“We have an average of 100 percent of students receiving employment after graduation,” Harrington said. “We have a very high student success rate.”

OU’s forensic chemistry program has been teaching students how to examine crime scene evidence for more than 30 years.

That could include analyzing drugs or explosive compounds.

The materials are acquired through two sources: donations from police agencies — when the evidence is no longer used in court — or chemical supply houses, Harrington said.

“We can buy these drugs in its pure form, but you need a license for it,” he said. “There’s a procedure to keep them in storage.”

OU holds two licenses — one with the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, which doesn’t charge, and the other with the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy, which has an annual $150 cost.

OU’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, which encompasses the forensic chemistry program, runs on a $3.7 million budget funded from the College of Arts and Sciences, according to Carolyn Khurshid, departmental administrator.

However, Glen Jackson, former OU director of forensic chemistry who left for a job at West Virginia University in 2012, said some drugs were previously purchased via Lipomed — a Swiss private health care company.

“We prepared (the students) for drug analysis,” Jackson said.

The Bureau of Criminal Investigation, located in Columbus, previously transported some narcotics to the university, Jackson said.

Local law enforcement agencies are typically legally bound to dispose of such evidence.

“We typically destroy our narcotics or it’s heavily controlled,” said Athens City Police Chief Tom Pyle. “We might divert them to a training program for K-9s, but that’s rare. Most of the time, we get court orders to destroy our drugs and they’re burned.”

Harrington said there weren’t any reported thefts from the storage supply or problems in the past but wouldn’t elaborate on where or how many drugs the university has in its possession.

“We have to have an inventory,” he said. “We don’t want to encourage people coming in and stealing it. Most of the samples they analyze end up getting burned or destroyed.”

With the program’s mock exercises, some students feel as if they’re getting the training they need to enter the workforce.

“I’ve had an internship at the Montgomery Coroner’s Office,” said Emily Antonides, a fifth-year senior studying forensic chemistry. “(The class) prepared you…it’s very similar to the real thing.”

The forensic chemistry class — unlike network crime shows such as NCIS — offers a true glimpse into the industry, Harrington said.

“Television shows you see are glamorous,” Harrington said. “The real world is not.”

hy135010@ohiou.edu

@HannahMYang